GSoC ’24: Enhancements to KomaMRI.jl GPU Support

Hi! 👋

I am Ryan, an MS student currently studying computer science at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Looking for a project to work on this summer, my interest in high-performance computing and affinity for the Julia programming language drew me to Google Summer of Code, where I learned about this project opportunity to work on enhancing GPU support for KomaMRI.jl.

In this post, I’d like to summarize what I did this summer and everything I learned along the way!

If you want to learn more about me, you can connect with me here: LinkedIn, GitHub

What is KomaMRI?

KomaMRI is a Julia package for efficiently simulating Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) acquisitions. MRI simulation is a useful tool for researchers, as it allows testing new pulse sequences to analyze the signal output and image reconstruction quality without needing to actually take an MRI, which may be time or cost-prohibitive.

In contrast to many other MRI simulators, KomaMRI.jl is open-source, cross-platform, and comes with an intuitive user interface (To learn more about KomaMRI, you can read the paper introducing it here). However, being developed fairly recently, there are still new features that can be added and optimization to be done.

Project Goals

The goals outlined by Carlos (my project mentor) and I the beginning of this summer were:

Extend GPU support beyond CUDA to include AMD, Intel, and Apple Silicon GPUs, through the packages AMDGPU.jl, oneAPI.jl, and Metal.jl

Create a CI pipeline to be able to test each of the GPU backends

Create a new kernel-based simulation method optimized for the GPU, which we expected would outperform array broadcasting

(Stretch Goal) Look into ways to support running distributed simulations across multiple nodes or GPUs

Step 1: Support for Different GPU backends

Previously, KomaMRI’s support for GPU acceleration worked by converting each array used within the simulation to a CuArray, the device array type defined in CUDA.jl. This was done through a general gpu function. The inner simulation code is GPU-agnostic, as the same operations can be performed on a CuArray or a plain CPU Array. This approach is good for extensibility, as it does not require writing different simulation code for the CPU / GPU, or different GPU backends, and would only work in a language like Julia based on runtime dispatch!

To extend this to multiple GPU backends, all that is needed is to generalize the gpu function to convert to either the device types of CUDA.jl, AMDGPU.jl, Metal.jl, or oneAPI.jl, depending on which backend is being used. To give an idea of what the gpu conversion code looked like before, here is a snippet:

struct KomaCUDAAdaptor end

adapt_storage(to::KomaCUDAAdaptor, x) = CUDA.cu(x)

function gpu(x)

check_use_cuda()

return use_cuda[] ? fmap(x -> adapt(KomaCUDAAdaptor(), x), x; exclude=_isleaf) : x

end

#CPU adaptor

struct KomaCPUAdaptor end

adapt_storage(to::KomaCPUAdaptor, x::AbstractArray) = adapt(Array, x)

adapt_storage(to::KomaCPUAdaptor, x::AbstractRange) = x

cpu(x) = fmap(x -> adapt(KomaCPUAdaptor(), x), x)The fmap function is from the package Functors.jl and can recursively apply a function to a struct tagged with @functor. The function being applied is adapt from Adapt.jl, which will call the lower-level adapt_storage function to actually convert to / from the device type. The second parameter to adapt is what is being adapted, and the first is what it is being adapted to, which in this case is a custom adapter struct KomaCUDAAdapter.

One possible approach to generalize to different backends would be to define additional adapter structs for each backend and corresponding adapt_storage functions. This is what the popular machine learning library Flux.jl does. However, there is a simpler way!

Each backend package (CUDA.jl, Metal.jl, etc.) already defines adapt_storage functions for converting different types to / from corresponding device type. Reusing these functions is preferable to defining our own since, not only does it save work, but it allows us to rely on the expertise of the developers who wrote those packages! If there is an issue with types being converted incorrectly that is fixed in one of those packages, then we would not need to update our code to get this fix since we are using the definitions they created.

Our final gpu and cpu functions are very simple. The backend parameter is a type derived from the abstract Backend type of KernelAbstractions.jl, which is extended by each of the backend packages:

import KernelAbstractions as KA

function gpu(x, backend::KA.GPU)

return fmap(x -> adapt(backend, x), x; exclude=_isleaf)

end

cpu(x) = fmap(x -> adapt(KA.CPU(), x), x, exclude=_isleaf)The other work needed to generalize our GPU support involved switching to use package extensions to avoid having each of the backend packages as an explicit dependency, and defining some basic GPU functions for backend selection and printing information about available GPU devices. The pull request for adding support for multiple backends is linked below:

https://github.com/JuliaHealth/KomaMRI.jl/pull/405

Step 2: Buildkite CI

At the time the above pull request was merged, we weren’t sure whether the added support for AMD and Intel GPUs actually worked, since we only had access to CUDA and Apple Silicon GPUs. So the next step was to set up a CI to test each GPU backend. To do this, we used Buildkite, which is a CI platform that many other Julia packages also use. Since there were many examples to follow, setting up our testing pipeline was not too difficult. Each step of the pipeline does the required environment setup and then calls Pkg.test() for KomaMRICore. As an example, here is what the AMDGPU step of our pipeline looks like:

- label: "AMDGPU: Run tests on v{{matrix.version}}"

matrix:

setup:

version:

- "1"

plugins:

- JuliaCI/julia#v1:

version: "{{matrix.version}}"

- JuliaCI/julia-coverage#v1:

codecov: true

dirs:

- KomaMRICore/src

- KomaMRICore/ext

command: |

julia -e 'println("--- :julia: Instantiating project")

using Pkg

Pkg.develop([

PackageSpec(path=pwd(), subdir="KomaMRIBase"),

PackageSpec(path=pwd(), subdir="KomaMRICore"),

])'

julia --project=KomaMRICore/test -e 'println("--- :julia: Add AMDGPU to test environment")

using Pkg

Pkg.add("AMDGPU")'

julia -e 'println("--- :julia: Running tests")

using Pkg

Pkg.test("KomaMRICore"; coverage=true, test_args=["AMDGPU"])'

agents:

queue: "juliagpu"

rocm: "*"

timeout_in_minutes: 60We also decided that in addition to a testing CI, it would also be helpful to have a benchmarking CI to track performance changes resulting from each commit to the main branch of the repository. Lux.jl had a very nice-looking benchmarking page, so I decided to look into their approach. They were using github-action-benchmark, a popular benchmarking action that integrates with the Julia package BenchmarkTools.jl. github-action-benchmark does two very useful things:

Collects benchmarking data into a json file and provides a default index.html to display this data. If put inside a relative path in the gh-pages branch of a repository, this results in a public benchmarking page which is automatically updated after each commit!

Comments on a pull request with the benchmarking results compared with before the pull request. Example: https://github.com/JuliaHealth/KomaMRI.jl/pull/442#pullrequestreview-2213921334

The only issue was that since github-action-benchmark is a github action, it is meant to be run within github by one of the available github runners. While this works for CPU benchmarking, only Buildkite has the CI setup for each of the GPU backends we are using, and Lux.jl’s benchmarks page only included CPU benchmarks, not GPU benchmarks (Note: we talked with Avik, the repository owner of Lux.jl, and Lux.jl has since adopted the approach outlined below to display GPU and CPU benchmarks together). I was not able to find any examples of other julia packages using github-action-benchmark for GPU benchmarking.

Fortunately, there is a tool someone developed to download results from Buildkite into a github action (https://github.com/EnricoMi/download-buildkite-artifact-action). This repository only had 1 star when I found it, but it does exactly what we needed: it identifies the corresponding Buildkite build for a commit, waits for it to finish, and then downloads the artifacts for the build into the github action it is being run from. With this, we were able to download the Buildkite benchmark results from a final aggregation step into our benchmarking action and upload to github-action-benchmark to publish to either the main data.js file for our benchmarking website, or pull request.

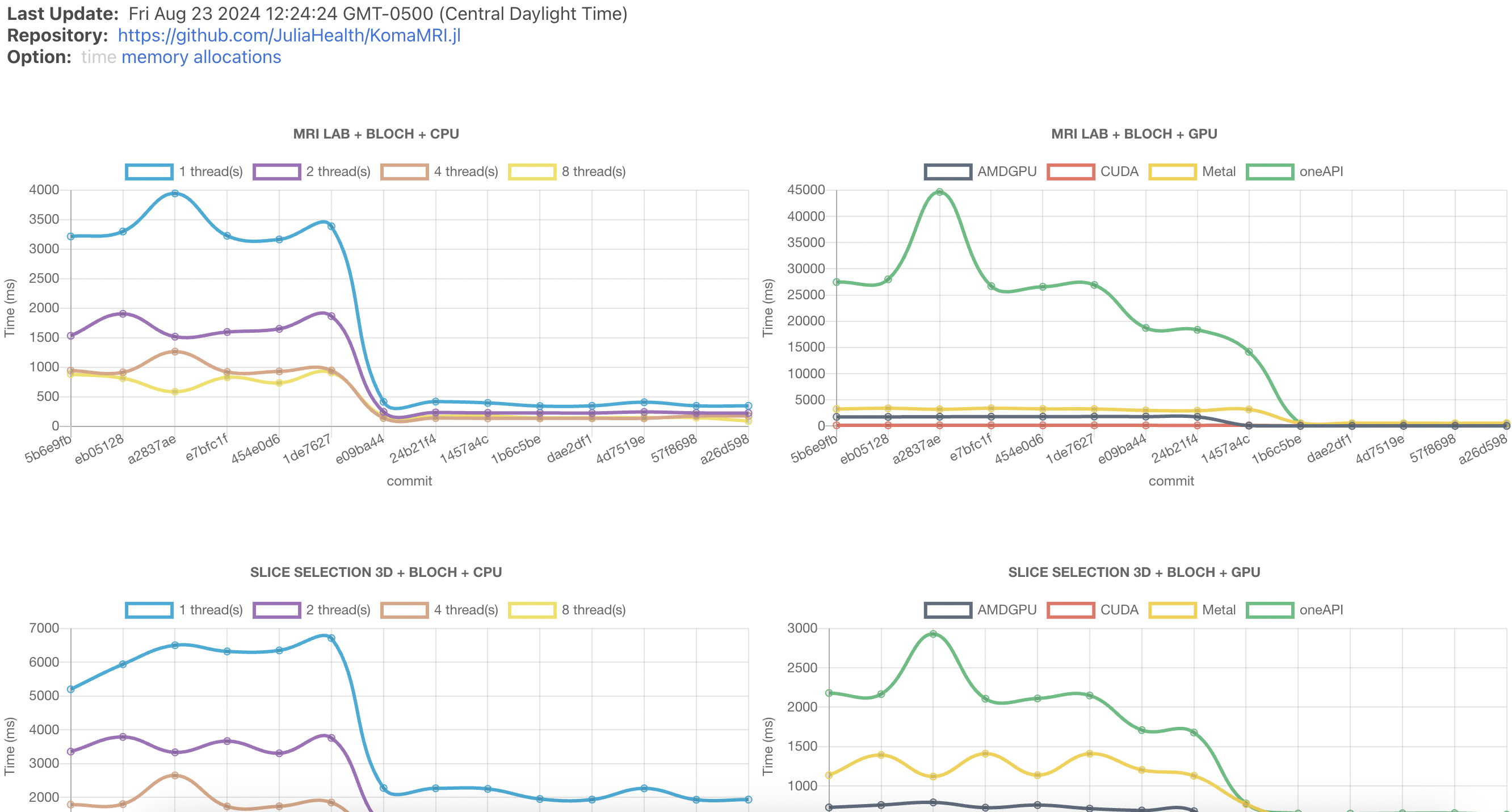

Our final benchmarking page looks like this and is publicly accessible:

One neat thing about github-action-benchmark is that the default index.html is extensible, so even though by deault it only shows time, the information for memory usage and number of allocations is also collected into the json file, and can be displayed as well.

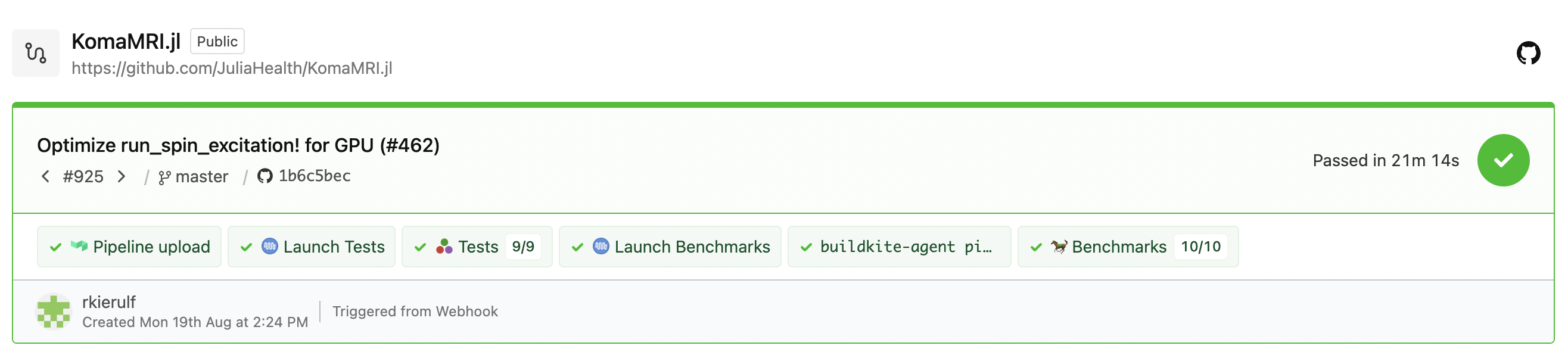

A successful CI run on Buildkite Looks like this:

The pull requests for creating the CI testing and benchmarking pipeline, and changing the index.html for our benchmark page are listed below:

- https://github.com/JuliaHealth/KomaMRI.jl/pull/411

- https://github.com/JuliaHealth/KomaMRI.jl/pull/418

- https://github.com/JuliaHealth/KomaMRI.jl/pull/421

Step 3: Optimization

With support for multiple backends enabled, and a robust CI, the next step was to optimize our simulation code as much as possible. Our original idea was to create a new GPU-optimized simulation method, but before doing this we wanted to look more at the existing code and optimize for the CPU.

The simulation code is solving a differential equation (the [Bloch equations(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bloch_equations)]) over time. Most differential equation solvers step through time, updating the current state at each time step, but our previous simulation code, more optimized for the GPU, did a lot of computations across all time points in a simulation block, allocating a matrix of size Nspins by NΔt each time this was done. Although this is beneficial for the GPU, where there are millions of threads available on which to parallelize these computations, for the CPU it is more important to conserve memory, and the aforementioned approach of stepping through time is preferable.

After seeing that this approach did help speed up simulation time on the CPU, but was not faster on the GPU (7x slower for Metal!) we decided to separate our simulation code for the GPU and CPU, dispatching based on the KernelAbstractions.Backend type depending on if it is <:KernelAbstractions.CPU or <:KernelAbstractions.GPU.

Other things we were able to do to speed up CPU computation time:

Preallocating each array used inside the core simulation code so it can be re-used from one simulation block to the next.

Skipping an expensive computation if the magnetization at that time point is not added to the final signal

Ensuring that each statement is fully broadcasted. We were surprised to see the difference between the following examples:

#Fast

Bz = x .* seq.Gx' .+ y .* seq.Gy' .+ z .* seq.Gz' .+ p.Δw ./ T(2π .* γ)

#Slow

Bz = x .* seq.Gx' .+ y .* seq.Gy' .+ z .* seq.Gz' .+ p.Δw / T(2π * γ)- Using the

cisfunction for complex exponentiation, which is faster thanexp

With these changes, the mean improvement in simulation time aggregating across each of our benchmarks for 1, 2, 4, and 8 CPU threads was ~4.28. For 1 thread, the average improvement in memory usage was 90x!

The next task was optimizing the simulation code for the GPU. Although our original idea was to put everything into one GPU kernel, we found that the existing broadcasting operations were already very fast, and that custom kernels we wrote were not able to outperform the previous implementation. The Julia GPU compiler team deserves a lot of credit for developing such fast broadcasting implementations!

However, this does not mean that we were unable to improve the GPU simulation time. Similar to with the CPU, preallocation made a substantial difference. Parallelizing as much work as possible across the time points for a simulation block was also found to beneficial. For the parts that needed to be done sequentially, a custom GPU kernel was written which used the KernelAbstractions.@localmem macro for arrays being updated at each time step to yield faster memory access.

The mean speedup we saw across the 4 supported GPU backends was 4.16, although this varied accross each backend (for example, CUDA was only 2.66x faster while oneAPI was 28x faster). There is a remaining bottleneck in the run_spin_preceession! function having to do with logical indexing that I was not able to resolve, but could be solved in the future to speed up the GPU simulation time even further!

The pull requests optimizing code for the CPU and GPU are below:

https://github.com/JuliaHealth/KomaMRI.jl/pull/443

https://github.com/JuliaHealth/KomaMRI.jl/pull/459

https://github.com/JuliaHealth/KomaMRI.jl/pull/462

4. Step 4: Distributed Support

This last step was a stretch goal for exploring how to add distributed support to KomaMRI. MRI simulations can become quite large, so it is useful to be able to distribute work across either multiple GPUs or multiple compute nodes.

A nice thing about MRI simulation is the independent spin property: if a phantom object (representing, for example a brain tissue slice) is divided into two parts, and each part is simulated separately, the signal result from simulating the whole phantom will be equal to the sum of the signal results from simulating each subdivision of the original phantom. This makes it quite easy to distribute work, either across more than one GPU or accross multiple compute nodes.

The following scripts worked, with the only necessary code change to the repository being a new + function to add two RawAcquisitionData structs:

#Use multiple GPUs:

using Distributed

using CUDA

#Add workers based on the number of available devices

addprocs(length(devices()))

#Define inputs on each worker process

@everywhere begin

using KomaMRI, CUDA

sys = Scanner()

seq = PulseDesigner.EPI_example()

obj = brain_phantom2D()

#Divide phantom

parts = kfoldperm(length(obj), nworkers())

end

#Distribute simulation across workers

raw = Distributed.@distributed (+) for i=1:nworkers()

KomaMRICore.set_device!(i-1) #Sets device for this worker, note that CUDA devices are indexed from 0

simulate(obj[parts[i]], seq, sys)

end#Use multiple compute nodes

using Distributed

using ClusterManagers

#Add workers based on the specified number of SLURM tasks

addprocs(SlurmManager(parse(Int, ENV["SLURM_NTASKS"])))

#Define inputs on each worker process

@everywhere begin

using KomaMRI

sys = Scanner()

seq = PulseDesigner.EPI_example()

obj = brain_phantom2D()

parts = kfoldperm(length(obj), nworkers())

end

#Distribute simulation across workers

raw = Distributed.@distributed (+) for i=1:nworkers()

simulate(obj[parts[i]], seq, sys)

endPull reqeust for adding these examples to the KomaMRI documentation: https://github.com/JuliaHealth/KomaMRI.jl/pull/468

Conclusions / Future Work

This project was a 350-hour large project, since there were many goals to accomplish. To summarize what changed since the beginning of the project:

Added support for AMDGPU.jl, Metal.jl, and oneAPI.jl GPU backends

CI for automated testing and benchmarking accross each backend + public benchmarks page

Significantly faster CPU and GPU performance

Demonstrated distributed support and examples added in documentation

Future work could look at ways to further optimize the simulation code, since despite the progress made, I believe there is more work to be done! The aforementioned logical indexing issue is still not resolved, and the kernel used inside the run_spin_excitation! function has not been profiled in depth. KomaMRI is also looking into adding support for higher-order ODE methods, which could require more GPU kernels being written.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank my mentor, Carlos Castillo, for his help and support on this project. I would also like to thank Jakub Mitura, who attended some of our meetings to help with GPU optimization, Dilum Aluthge who helped set up our BuildKite pipeline, and Tim Besard, who answered many GPU-related questions that Carlos and I had.

Citation

@online{kierulf2024,

author = {Kierulf, Ryan},

title = {GSoC ’24: {Enhancements} to {KomaMRI.jl} {GPU} {Support}},

date = {2024-08-30},

langid = {en}

}